Saying goodbye to a Liberian football legend

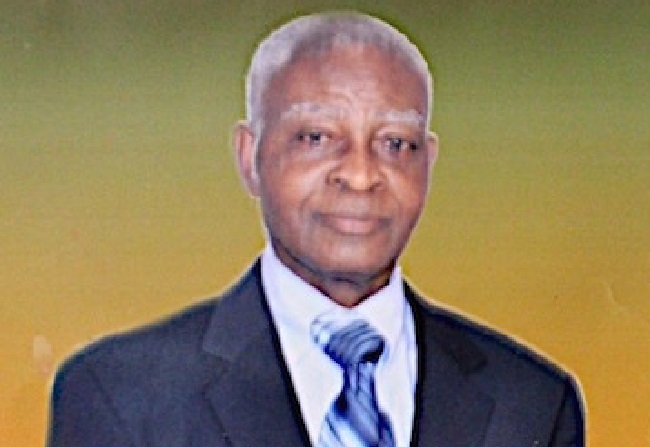

Philip Robinson was one of Liberia’s greatest football players

Photo: tlcafrica.com

In recent years, the Liberian football community has lost some of its most prominent individuals to death. Those who have travelled that road gently are Mass Sarr, Garretson Sackor, John “Monkey” Brown, George Sackor, Gladstone Ofori, David Momo, Philip “Cocha” Davis, etc. They have now been joined by Mr. Philip Robinson. Mr. Robinson’s family, with the deepest of sadness, announced to the public that he passed away on July 14, 2017, at the Hopkins Manor Nursing Home in Providence, Rhode Island; Benedict Nyankun Wisseh writes.

To anyone who does not follow the business of Liberian football history, Mr. Robinson’s name will only draw an ordinary reaction followed by the usual saying of “the name rings a bell.” Then, because it is what we have to say when it comes to death, the person will politely conclude with another usual saying of “may his soul rest in peace.” But, for us who follow the history of Liberian football, Mr. Robinson was not an ordinary Liberian because of his lifelong and selfless contributions to make Liberian sports better.

Mr. Robinson’s death is not a simple loss. The reasons for which it is not a simple loss are not told in careless embellishments. In May, this year, I had a conversation with Liberian football icon, Borbor Gaye, in Newark, New Jersey. Our conversation was primarily about Mr. Gaye’s past as a footballer. He recounted how he started to play football and develop to become one of Liberia’s greatest football players. But as he spoke about this section of his biography, he repeatedly mentioned Mr. Robinson as “a good coach and wonderful man.” Mr. Robinson, he stated, “was instrumental” in his development as a player. What he got to understand about playing football, while he was a member of the Liberian junior national team, was thought to him by Mr. Robinson, Mr. Gaye said.

“Like a teacher,” Mr. Gaye said, ” Robinson saw how good I could be as a player. Therefore, he always advised and encouraged me to work harder. Through demonstrations, he pointed out my mistakes and told me how to correct them.” This account of Mr. Robinson mentoring young players is corroborated by my own experience as a player in the 1970s.

In 1976, I debuted for Bameh at the Antoinette Tubman Stadium (ATS) against Cornerstones from Ghana. Mr. Robinson, who was by then a certified Federation Internationale de Football Association (FIFA) referee, was assigned as the referee. About ten minutes into the game, I scored for Bameh and thought that I was doing well. But the linesman kept raising his flag on me for offside. I did not understand why I was being called offside. Perhaps, after the third conservative call against me for offside, Mr. Robinson, while running backwards pass me, he said “son you are lacking behind the defenders after your attack.” I clearly heard what he said. But I did not understand what he meant and went on repeatedly making the same mistake and, repeatedly, I was called offside. For the record, we lost 2-1.

On Monday, unknown but feeling good about my performance on Sunday, I went to the ATS to watch Barrolle Vs Cornerstones game. There, I ran into Mr. Robinson and, very politely, he engaged me in a conversation about my performance.

While he praised my performance, he pointed out my flaws. It was in this conversation that he explained to me why I was called offside repeatedly. Mr. Robinson was fatherly and polite, at times resting his hands on my shoulders, as we stood face-to-face, to make sure that I understood him.

In the four years I played football on the national stage in Liberia, Mr. Robinson always praised me. But he did not hesitate to point out my mistakes and recommend corrections. He always ended every conversation with “so, young man, don’t forget to work on that.”

Mr. Robinson had his own credential as a footballer, too. Apparently, this inspired his commitment to the development of Liberian football and how well players played.

According to Charles Wordsworth, the Liberian sports historian and former national basketball star, Mr. Robinson began his playing career in the 1950s with Youth Leaders, a leading team in Liberia at the time. Some of his contemporaries were Samuel Hodge, Henry Varfley, Bruce Smith, Leonard Deshield, Gideon Gadegbeku, David Wolo, Peter Williams, Sam Elliott, Albert Johnson, Francis Lawson, Anthony Dixon, Reubel Brewer, MacDonald Acolaste, and Aloysius Itoka.

It was the period of this generation that the first game of the “County Meet” was played in Monrovia. As a player, Wordsworth described him as a “very intelligent” midfielder who influenced the outcomes of games in his team’s favour on many occasions. Such was the case in the 1956 “County Meet” tournament that he was voted player of the tournament. This performance, apparently, led to his unanimous election by his peers as captain of the national team in 1957.

Following his retirement from playing football, Mr. Robinson was sent to Germany, where he studied sports administration and coaching. He returned to Liberia and began working with the erstwhile Sports Commission as a football coach.

Having impressed in this role, he was selected, under a programme between Liberia and America, to coach at Beloit College in Wisconsin in the early 1960s. This, according to Wordsworth, makes Mr. Robinson the first Liberian to coach at an American college as a head football coach.

He completed the coaching assignment there as the college winningest coach at the time. He returned home and resumed coaching until the mid1970s when he was appointed chief liaison at the Sports Commission.

In this position, although a football man, he represented the interests of all sports equally, executing his responsibilities via public transportation or an office car, if one was available and, sometimes on foot.

Just before the 1970s ended, he was appointed assistant director of sports in the Ministry of Labor, Youth and Sports. His selfless commitment to the development of all sports did not go un-noticed and unappreciated. This led to his appointment as assistant minister for sports at the Ministry of Youth and Sports (MYS).

In a long line of service to Liberia and its sports, Mr. Robinson became and served as a referee. But he was not just an ordinary Liberian referee. He was also an African referee trusted by all, inside and outside of Liberia, because his understanding and enforcement of football rules inspired that trust.

On the African continent, where suspicious questions are raised about the integrity of referees, Mr. Robinson was an exception. There was never a time that his name was speculated in any dishonest conduct as a referee, nor was he criticised and punished for making ball calls.

Throughout the life of his referring career, he commanded praise for his authoritative and respected control of football games. Mr. Charles Verdier, a protégé of Mr. Robinson’s, described his mentor as a “very honest man.” Mr. Verdier, who went on assignments with him to other countries, told me that Mr. Robinson always reminded him and his colleagues that in the business of referring, integrity is essential.

Mr. Robinson did not only preach it, he practised it and won the confidence of FIFA and African football authorities that he was assigned to handle important games on the continent. In the 1970s, he was assigned to serve as referee for a final of the African Cup of Nations Championships, making him the first Liberian referee to undertake such football assignment.

In any other country, Mr. Robinson’s accomplishments would have made him an honoured hero. His death would have made the headlines on the front pages of the daily newspapers. The members of the cabinet and parliament would have stood up to observe a moment of silence followed by an official proclamation publicly announcing his death. But in Liberia, it does not happen. No Liberian newspaper mentioned his death either in its middle or back pages.

This failure by the papers, perhaps out of ignorance of Liberian football history, can be forgiven with reluctance. However, this forgiveness cannot be extended to the Ministry of Youth and Sports and the Liberian Football Association (LFA) because they are respectively responsible for the business of sports in general and football specifically. For this reason they are obligated, at least, to put out an announcement of the death of a former player. But the LFA, under the presidency of Musa Bility, undoubtedly, sees its mission to be organising football games only.

As I say goodbye to Mr. Robinson, in the silence of LFA and MYS over his death, I am pleased to assert that I will remember him as a referee who inspired confidence in me that my team was not going to lose a game because of his errors or cheating. I believed in his decisions because he was an honourable man, a counselor, statesman, and hardworking public servant, qualities that made him a good Liberian. REST IN PEACE, PHILIP SWEN ROBINSON!

Benedict Nyankun Wisseh is a graduate of the defunct Charlotte Tolbert Memorial Academy. Email: bnwisseh1107@gmail.com