Consulate creates problems for Liberians

If you are a Liberian residing in the United States, and in need of Liberian travel documents to fly out of the country at a short notice, the Liberian consulate at 866 United Nations Plaza, New York City, isn’t the place to go. That’s because, operation at the consulate is marred by red-tape bureaucratic procedures so much that scores seeking new ECOWAS Liberia biometric passports to travel have been forced to cancel their trips due to delay; writes James Kokulo Fasuekoi

In Shambles

Our staff writer, who visited the Liberian embassy last month in an attempt to obtain a passport that would facilitate his travel abroad, observed that the process to get a travel document from there can sometime be awfully slow. Although information at the consulate’s website indicates duration to be between 3-6 weeks, some can actually take two months or more.

In addition, The AfricaPaper also discovered that the diplomatic mission is in shambles. The consulate section where interviews are done appears too small for customers. Besides, several customers complained the interview process is characterized by a total lack of courtesy and privacy, situations that caused them to feel frustrated. At the center of it all is one Kim Greene-Konneh, a vice counselor at that embassy.

Terence and Klubozumo

On April 14, 2015, a Liberian, Terence made a follow up visit to the consulate in New York, having applied for a passport online. Like other applicants, Terence went through the interview process and after a few hours, left for home, hopping to get his passport through the mail to enable him travel in time.

But, when contacted on May 20, Terence told TAP that his passport came in his mail three weeks later. Of the many passport seekers who apply for Liberian travel documents at the consulate weekly, Terence seems to be among the lucky ones because, for some, the processing period might take up six weeks to two months.

Another Liberian Klubozumo, of the New York-New Jersey area wasn’t so lucky. Klubozumo’s passport, according to his wife, took more than two months before he finally received it.

But before then Klubozumo, worried that he could likely miss his scheduled trip to East Africa due to delay as his traveled date approached, returned to the consulate and applied for a Lessee Passé just as the first month ended. The Lasse Passé which should have been done immediately instead, took another week before he got it. His wife told TAP at the embassy that, it happened because her husband went back for a third time and insisted he would not leave till he gets his temporary travel document.

Personal Experience

On the same April 14, I had gone to the New York Consulate to go through the application and interview process to obtain a travel document in order to facilitate my trip abroad. The new procedure through which one can get a Liberian passport has become very tedious and of course costly apart from a $205.00 fee being charged by both consulates in New York and Washington D.C.

Having received a greenlight for my trip at short notice and seeing there was no vacation time left at hand on the job, I was forced to turn what would normally be a four-day journey (to and fro) by car from Minneapolis, Minn., to New York City, into a three-day trip and often risked driving between sleep and wake.

But what was perhaps more disappointing was after a counselor informed me that the normal processing period for a new Liberian passport could take from 3-6 weeks. They said that expedited services only apply to visa processing and passport renewal/extension, and not replacement of old Liberian passport with the new ECOWAS designated biometric type.

I quickly pleaded with Kim Greene-Konneh to treat my case as an exception and speed up the process due to the urgency and important nature of the trip which was scheduled for April 28. Konneh refused at first and remarked in the presence of customers, “We [staff] go by rules here …we don’t do things the Liberian way.” That meant I would have to wait out the 3-6 weeks duration like every other applicant.

Meeting Konneh

Following an initial interview, I later sought audience with Kim Konneh in her office during which I gave her a better insight about my then pending trip abroad, placing emphasis on the trip’s timing and urgency. I also showed her emails from the inviting party as proof of authenticity. She then dubbed my case a “special case,” and advised me to wait and stay last so she could address my passport matter. I agreed.

After finishing application process and interviews, I left without any assurance from Konneh as to when it would be ready. The two weeks that followed I bombarded the consulate with phone calls. Hananatu Tunis, a young office assistant, and courteous woman, received bulk of my calls and in turn passed them on to Konneh as messages.

At one point, Konneh picked up my call, and at another time, she responded to a voice message from me to let me know how far the process had gone. Before then I had thought that the consulate had new unprocessed passports available at its New York Consulate that could be issued out to applicants at any moment but that wasn’t the case.

Under the new system, as gathered, the new passports being issued to applicants here can be processed in Liberia based on the number of application submitted with paid fees. Afterwards, the passports are then shipped to the United States and mailed to the owners. Sounds ridiculous!

In spite of the numerous calls and frantic effort, mine finally arrived on April 29, in the mail. Exactly a day after my scheduled trip expired. Mine apparently, was quicker and some might even say I was perhaps one of the luckiest persons.

Crowded Customers

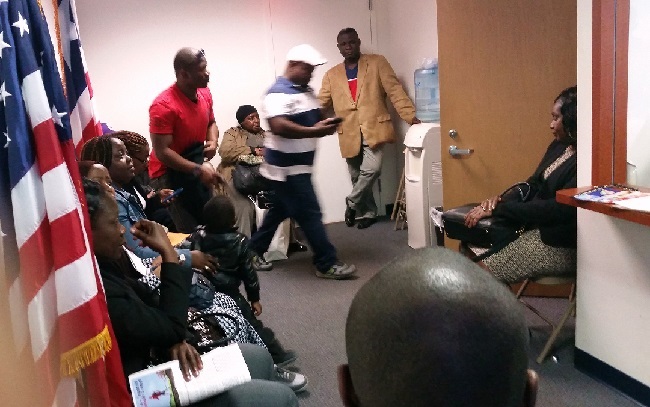

The consular section at the New York Embassy where interviews are conducted appears just too tact to hold ten or more persons. Yet on any business day, one can count 14 to 15 customers occupying the small room at any given time. And often, chairs are in short supply, thus leaving some with no alternative but to stand in the room.

On my April 14 visit, about 16 customers (including non-Liberian visa seekers), waited there patiently to be served. More than half were forced to stand for at least an hour or more while waiting for their passports or visas to be processed.

The consular office is a tiny space that customers are forced to sit in circle, where one could even stretch his hand and reach out to the person sitting in front of him or her.

Lacking Privacy

The distance between the customers and the main counter where the interview takes place isn’t more than a four yard stretch. As a result, every customer in the room gets to listen to the interviews thereby keeping a record of the life stories of fellow passport and visa applicants.

There’s never anything like “privacy” and it’s practically like a nurse or a doctor having a patient to explain his or her medical condition before a crowd of patients in a hospital waiting room, something that would contradict HIPPA rules, thereby resulting to serious lawsuit in these United States.

Such unprofessional and “open style” interview or treatment caused Liberians, and Liberian-Americans present at the embassy made them grumbled among themselves with some openly voicing out their disapproval in hearing distance of the embassy staff.

Humiliation

Of the numerous interviews carried out by Kim Konneh on April 14, one in particular that every visitor will vividly remember is that of a middle aged Liberian woman whose grandparents were Ghanaians. She said the grandparents later resettled in Liberia where they bore her father.

She told the interviewer that she spent a very short time in Liberia before she migrated with her father to the United States years before the country’s brutal war struck. Her father, she maintained, later died in the U.S. This situation she said left her with a thin memory of her native Liberia except for schools she attended.

Though the lady spoke with a clear Liberian accent, she had difficulty convincing Konneh regarding her Liberian nationality in her quest to acquire a Liberian passport. Her interview was gluing and in most cases, demeaning.

She was requested to tell places she lived and schools attended in Liberia as well as friends she may have had prior to coming to the United States.

Konneh’s point was that just by one being born in Liberia onto a family with foreign origin doesn’t make one a Liberian. But the more the lady sought to provide a proof of her nationality, the more Konneh pressed further for more evidence.

Liberian Constitution

When the woman cited the St. Theresa Convent School in Monrovia as the place she acquired her early education, Konneh asked the lady: “Don’t you know your constitution?” in an apparent reference to the section of the Liberian Constitution under Chapter IV, Article 28 which states below in parts:

“Any person, at least one of whose parents was a citizen of Liberia at the time of the person’s birth, shall be a citizen of Liberia; provided that any such person shall upon reaching maturity, renounce any other citizenship acquired by virtue of one parent being a citizen of another country.”

In another incident, Kim Konneh was heard telling another Liberian-American woman “Don’t you read your constitution?” The lady had gone to the embassy to seek visa for her American born child she plans to take along to Liberia. But for some reason, she purchased only a one-way air ticket for the child.

According to US law, before a parent can have an American citizen who is a minor to travel out of the country, he or she must provide a round-trip air ticket for the person. Confronted over this by Konneh, applicant explained, her husband had died and due to that she was taking the child to Liberia for now but would get her back to the states afterward when she readjust.

Konneh set forth one condition in order to give the child a Liberian Visa. The child’s mother was requested to write a letter to the consulate and state reasons why she couldn’t buy round-trip ticket for the child at this time. The mother refused on ground she couldn’t write and instead asked the vice counselor to write on her behalf.

“Arrogant Diplomat”

What some see as interesting and problematic about the vice counselor during these interview sessions firstly, is her habit to interject a bloated image of herself regarding her academic background, coming down to how she trained at the Foreign Affairs Ministry for the job she’s currently performing.

Secondly, she seems to hold the belief that everyone born in Liberia, whether schooled or not, ought to have a clear interpretation of the constitution to his finger-tip, not to mention academicians like lawyers, doctors, politicians and journalists, which of course is far from the truth. Such behaviors had some leaving with the impression that Konneh is an “arrogant diplomat.”

Many Liberian-Americans, who watched both interviews, scorned Counselor Konneh for her “interrogative style” interview. Some even compared them to the demeaning ways counselors at the US. Embassy in Monrovia often conducts interviews with people who seek visas to enter the United States.

They complained and criticized Kim Konneh for what some termed her “lack of courtesy and respect” for fellow Liberians during her interview process. A man who preferred not to be named argued: “She [Konneh] treats Liberians as if they are foreigners seeking visa or travel document to visit the homeland.”

“Americans, on the other hand hold their citizens in high-esteem and would never treat their fellow Americans in such humiliating ways, so why will Mrs. Konneh treat Liberians with disrespect,” remarked another applicant.

Preference for US citizenship

Due to the current terrible state of processing passport at the consulate, many Liberians who previously felt reluctant about applying for US citizenship appear now to have changed their minds.

A few who were spotted venting their emotions in the presence of the embassy’s staff said they will go ahead to seek U.S. citizenship without delay in order to cut off the “unnecessary bluff.” As they spoke, vice counselor Konneh and her staff continued work behind the thick bullet-proof glass panel that separates an interviewee from the interviewer.

Liberians, mostly naturalized Americans, or with dual citizenship, normally obtain Liberian travel documents for travel purposes and the reasons are twofold: The first is, it prevents one from overusing his US passport when traveling overseas in that it also attracts financial extortion and is highly sought by criminals. The next is it helps eliminate the usual US $200.00 or more for a visa fee especially for numerous countries in Africa, including Liberia.

Examples from Nigeria and U.S.

In and outside of Liberia New York Embassy, the argument continues that while other countries like the United States and Nigeria seek to make things like passport processing for their respective citizens cheap and accessible, Liberia and its officials, on the hand, have the habit of making things harder for Liberians always.

The U.S. for example, has made its passport accessible and affordable more than ever before so much so that one can even take advantage of “Same day processing” otherwise referred to as 24 hours service around the US, with only a few exception to States such as Florida and perhaps, California.

In addition, there are varieties of expedited services that could take only eight business days or less for the passport to arrive just by paying a little extra which is fair than pay a fortune. Almost every postal office within every neighborhood in the United States now serves as a passport bureau where Americans can even walk and apply for passport, pay a minimum fee of $60.00 and expect it within two weeks or less for regular service.

For Federal Republic of Nigeria, it decided to transport its Washington D.C. passports crew to Minneapolis, Minnesota, (the US state with the highest African immigrants), last year to give out to her citizens the same ECOWAS passports for as little as US$50.00 each. The team was in the state for days and the exercise was meant to cut down unnecessary travel expenses, inconveniences as well as loss time on the job for her people because that government seems to considers the interest of its citizens paramount.

Weeks before the passport team could arrive in Minneapolis, the embassy’s officials had sent out announcements to their people at every African worship center in the state regarding the crew’s visit, urging all Nigerians to carry their children as well as grandchildren who might desire a Nigerian travel document, to get it at the same rate.

Criminals Taking Advantage

The tedious process that Liberians in the U.S. presently face in order to obtain Liberian travel documents has opened doors for certain unscrupulous individuals back home in Liberia to exploit fellow Liberians living abroad, particularly, the United States.

For example, a Liberian man who goes by the initials GC, persuaded me some time ago to send him money so he could process a passport for me in Liberia. This is despite the fact that one of my close relatives who lives in Liberia, checked it out and told me the new process couldn’t work without my presence in Monrovia.

But GC, aware of how desperately I needed a new passport to travel, assured anyhow he could get me one. All that he needed me to do is, pay an extra amount beyond the “official fee” which was US$23.00 at the time. He charged a total of US$125.00 and explained the amount would also covered “expedited services” since according to him, I was unable to be physically present in Liberia for the fingerprints process.

That was in late February when we had the conversation. GC works with the Liberia’s National Bureau of Immigration and Naturalization (BIN). Also a man I personally met through my children when I was in Liberia in 2012. He assured that he had a contact at the passport bureau to do the work.

For me, this was good news for it could save me from a lot of things. Meaning, it would prevent me from buying air tickets for about $450.00 to $500.00 at short notice in order to fly to New York City and back. It meant also that I didn’t have to worry about taking days off work, nor did I need to pay for car rental while in New York. Besides, it would also stop me from paying US $205.00, for the same product (passport) now sold at $50.00 in Liberia.

Without hesitation, on March 5, 2015, I wired the money to GC via Money Gram in the amount he had requested, then texted him the controlled number to collect the money. He texted back the next day at exactly 3:20 p.m. Liberian time and confirmed he received the money. Since then almost three months the passport hasn’t been processed nor has GC discussed about refunding me.

He no longer calls, and doesn’t pick up my calls. Although GC, prior to sending the money often called me almost daily. GC isn’t alone in this act; there are other “GCs” and victims and one won’t know till he starts to discuss his personal experience with people within the Liberian community.

In all, I spent more than $1,000.00 just to obtain a Liberian passport. That’s excluding lodging, in addition to using my personal vehicle to avoid payment of car rental charges to and fro New York.

MFA Could cut down on Losses

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) of the Republic of Liberia has the power to minimize the ridiculous cost for travel, plus the constant headaches Liberians all over the United States currently experience just to travel to and fro New York and Washington D.C. in order to obtain a Liberian passport.

They could choose either of the following two options. They can choose to adopt the Nigerian example. Or MFA could establish a system whereby both Liberia consulates in New York and Washington D.C., would have Liberian passport applicants do their biometric and fingerprints at a local police station or FBI headquarters and then submit same to the consulate.

This method is credible and it is the same system local law enforcement agents including the FBI, use to do criminal background checks for certain jobs here. If considered, it could prevent people from traveling long distances and spending a fortune, like in the case of this writer, in order to get a Liberian passport.

James Kokulo Fasuekoi is Associate Editor for The AfricaPaper based in Brooklyn Center, Minneapolis, Minn. He can be reached at: fasu@theafricapaper.com