How does South Sudan move forward?

Fleeing fighting in South Sudan

Photo: C. Tijerina/UNHCR

Although a ceasefire between rival forces in the South Sudanese capital, Juba, is largely holding, the underlying tensions that led to five days of deadly violence earlier this month remains unaddressed.

So what happens next?

Amid the many dire warnings that South Sudan is about to dissolve into civil war, a small comfort is that it hasn’t happened yet.

The mass ethnic killing of civilians in Juba that occurred in December 2013, marking the start of two years of terrible conflict, has not taken place. Apart from some pockets of trouble, the violence has not spread, and “we have seen some restraint from the leaders”, said Casie Copeland of the International Crisis Group.

There was 30 minutes of wild gunfire on 11 July when President Salva Kiir’s SPLA forces celebrated the defeat of rival Riek Machar’s soldiers in Juba. Deep animosity remains between the two camps, and there are believed to be those within the ruling circle urging Kiir to go ahead and finish the job.

Although the military option “will always be on the table, the towel has not been thrown in yet on the peace agreement”, said Copeland.

Rebuilding trust

But resuming negotiations in the current climate of fear and rumor, with Machar in hiding and his ministers holed up in various hotels in the city, will require a Herculean effort of confidence-building.

“Right now, I can’t imagine that these two men want to say anything to each other that’s even remotely constructive,” said a Juba-based analyst, who asked not to be named. The idea of joint patrols by soldiers of the SPLA and Machar’s SPLA-IO, as envisaged in the peace agreement, seems preposterous.

“Right now, people need time to acclimatise,” said the analyst, unwilling to give his name after the arrest of veteran journalist Alfred Taban at the weekend by SPLA soldiers after calling for Kiir and Machar to resign. “There needs to be enough physical distance between the forces, otherwise they will tear into each other.”

However imperfect, the power-sharing agreement negotiated in Addis Ababa is the only framework there is for peace.

After the deaths of close to 272 people and the displacement of 36,000 by the fighting, what is sorely lacking now is trust.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has called on the Security Council to approve more troops to the UN Mission in South Sudan (UNMISS) to better protect civilians. At the current time, the much-derided 12,000-strong peacekeeping force can only conduct “limited patrolling”.

Intervention brigade?

The regional Intergovernmental Authority on Development has called for an “ urgent revision” of the UNMISS mandate to establish a more robust “intervention brigade”, manned by additional troops from the region. In a communiquè on Saturday, the eight-nation group called for the force to “separate the warring parties, protect major installations, the civilian population and pacification of Juba”.

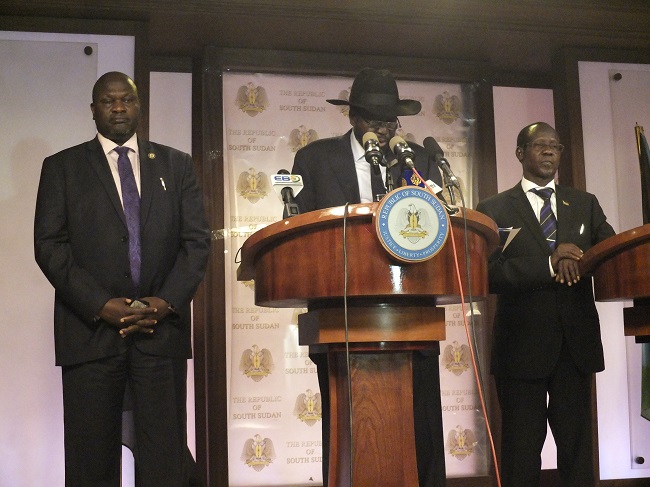

South Sudan President Salva Kiir (in hat) with Vice President Riek Machar (left) and Vice President James Wani Igga at a press conferenceas fighting broke out on 8 July. Photo: Samir Bol

But if the deployment is part of UNMISS and paid for by the UN, then getting those additional boots on the ground could take between six to seven months.

“IGAD has called for the UN to build an intervention brigade, but it’s not going to happen any time soon,” said Malte Brosig, a peacekeeping specialist at South Africa’s University of the Witwatersrand. “The UN is extremely reluctant to take on something like this.”

The more immediate concern is that Kiir has warned he will not accept any additional foreign soldiers. That has not stopped Uganda sending in its soldiers to rescue its nationals, but the touchy issue of sovereignty may well resonate for some Security Council members, including Russia and China.

Regional support

Members of an intervention force, likely made up of troops from Ethiopia, Kenya, Uganda, and Rwanda, are not going to be expected “to fight their way in”, said Cedric de Coning of the Norwegian Institute of International Affairs. It will have to be part of a peace process in which both Kiir and Machar “stand down their forces in a demilitarised Juba”, he explained.

Achieving that goal “will be the [diplomatic] dance”, said Copeland. She sees the first step as possibly being regional troops guaranteeing Machar’s protection, alongside talks on a broader military intervention.

UNMISS has little credibility in South Sudan, but the country’s neighbours have influence. IGAD’s heads of state (with help from some key Western governments) have invested hugely in the peace process and are determined to see it work. “Stabilising South Sudan stabilises their own [national] interests in the country,” said one analyst.

Political dynamics

Much has been written about the apparent fragmentation of power in South Sudan. On Kiir’s side, the figure of hardline Chief of General Staff Paul Malong Awan looms large, as does the alleged influence of the Council of Dinka Elders.

Machar, on the other hand, is believed to have lost the support of commanders in his SPLA-IO movement long before the peace deal was signed. “This is not a two-man show, but a very complex landscape now,” said the Juba-based analyst. Central control has never been strong in South Sudan, but its bankrupt economy and the current political and military instability are making it a good deal weaker.

But Copeland believes there are moderate voices on both sides that could help steer the process. She argues that the mistake IGAD made was to lose sight of the implementation of the agreement, particularly over issues such as demilitarisation, cantonment areas, and tensions around the boundaries of new states decreed by Kiir.

International levers?

The traditional response from the international community when confronted by truculent parties to a peace deal is to threaten sanctions. Western governments waived that stick during the sticky stages of the talks in Addis Ababa. Ethiopia, the leader of the IGAD process threatened, perhaps apocryphally, to lock both parties in their hotel to get an agreement.

But neither approach delivered a sustainable peace. It also unhelpfully created the expectation in Juba that a government of national unity would be rewarded with a flood of Western aid and financial support – which failed to materialise. The donors were waiting for progress on a list of their demands.

“It’s now unhelpful at this stage to talk about sanctions,” said Rashid Abdi, also with the ICG.

Underlining that sentiment, the region has already turned its back on Ban’s idea of an arms embargo.

“An arms embargo would also destroy the local force on which a strong, integrated national army should be built,” Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni reasoned, rather strangely, in a tweet.

“There is no other acceptable alternative to talking,” said Abdi. “But we don’t have to start at Ground Zero. We have a framework. We just need to resolve the issues around cantonment, integration, and power-sharing that led to the violence.”

IRIN