Hate speech stirs trouble in Burundi

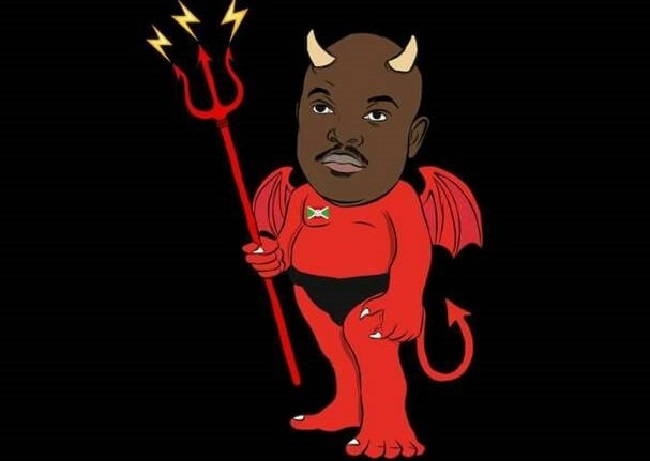

Burundi President Pierre Nkurunziza portrayed as a devil on facebook

Next month, the Commission of Enquiry on Burundi, established by the UN Human Rights Council, is due to deliver its final report on abuses in the central African state and to make a judgement as to whether these abuses, including killings, torture, and abduction, amount to international crimes.

The commission has highlighted the prevalence of hate speech in Burundi, notably by the ruling party and its affiliates, saying such rhetoric, which often targets specific ethnic groups, “reinforced” human rights abuses. It has called for the state to take action against perpetrators.

In 2015, an announcement by President Pierre Nkurunziza that he would stand for a controversial third term plunged the country into crisis, marked by violent clashes between protestors and security forces, a failed coup, and the flight of hundreds of thousands of people out of the country.

Burundi continues to present numerous risk factors of further violent destabilisation and hate speech remains widespread, especially on social media, while authorities appear to being doing little to curtail it.

Facebook posts and comments, some using pseudonyms others by people apparently using their real names, routinely contain blatant incitement to violence.

“Hutus are filth and we will keep killing them if the opportunity presents itself,” read one recent Facebook post by someone calling himself “Ntwari Alexis”. The profile picture shows a man sitting on an armoured car brandishing the national flag of Burundi.

Since “Ntwari” means “brave man” in the Kirundi language, the name is presumably fake. The post appeared the day after the second anniversary of the assassination in a rocket attack in Bujumbura of General Adolphe Nshimirimana, a former intelligence chief and right-hand man to Nkurunziza.

Role reversal

During Burundi’s 1993-2006 civil war, which pitted a range of Hutu rebel groups against the Tutsi-led government and army, Nshimirimana served as the military commander of the CNDD-FDD, a Hutu insurgency that transformed itself into the political party now in power.

On Twitter, one Diana Nsamirizi wrote recently of the country’s Tutsi minority (who dominated power between independence and the end of the civil war): “Now it’s your turn. I want you to flee [the country] and see what it’s like. You’re conceitedness will end one day.”

Another poster on Facebook wrote: “All the problems the country has had were caused by the Tutsi… The Tutsi are difficult to live with. They are proud. They overestimate themselves. They are the descendants of Cain. The Tutsi massacred Hutus in 1968, 1972, 1994-2004. We must not forget these troubles and above all those who caused them.”

A message posted by a 20-strong group on the social media network in mid-June went even further, declaring: “We are determined to fight the mujeri until they give up their beastly ways.” The Kirundi word mujeri is a derogatory term for stray, dirty dogs, in this case applied to opponents of the regime. “Mujeri are little dogs which bite people,” the Facebook post continued. “To eradicate the mujeri, they must be chased, even in their hiding places.”

Specific threats

In yet another post, “mujeri” was applied to certain prominent foreigners in Burundi, including US Ambassador Ann Casper: “Behead those mujeri,” wrote someone using the name “Eustache Tiger”, a vocal supporter of the president.

Also among the targets of violent threats has been former president Domitien Ndayizeye, after he spoke out against the Imbonerakure, the ruling party’s youth wing, which gained notoriety earlier this year when 100 of its marching members chanted that female opposition supporters should be raped or even killed. Human Rights Watch has accused the Imbonerakure of being involved in the gang rapes of women and the torture of opposition members.

After the former president criticised the slogans of the youth wing, Sylvestre Ndayizeye (no relation), who coordinates associations affiliated with the ruling party, warned his namesake that should he continue to “insult” the Imbonerakure, “we will deal with him”. He used the Kirundi verb

“gukorerako”, which in the slang of the youth wing, which harks back to the language used by rebels during the civil war, means to kill.

Burundi’s penal code outlaws such declarations, according to jurist Pacifique Manirambona. “The state prosecutor or his office is supposed to take up such matters, initiate investigations, and prosecute those behind such hate speech,” he told IRIN.

“Defamation, or hatred against a group or people or a segment of the population, causes social problems and endangers lives. Insults or describing individuals or groups as animals [or] cartoons depicting people as animals are degrading and should be punished under law,” he added. As well as “stray dogs”, targets of hate speech in Burundi have been described as snakes, refuse, and excrement.

Dehumanisation

Political scientist Jean-Marie Ntahimpera warned that resorting to animal terminology was “very dangerous. We saw it during the [1994] genocide in Rwanda. The Tutsi were called inyenzi, cockroaches, before being killed.”

Dehumanisation is one of the 10 stages of genocide identified by Gregory H. Stanton, the president of Genocide Watch. According to The Genocide Report, “dehumanization overcomes the normal human revulsion against murder…. [One group] is taught to regard the other group as less than human, and even alien to their society. They are indoctrinated to believe that ‘We are better off without them.’ They are equated with filth, impurity, and immorality.”

That dehumanisation, and other phenomena among the 10 stages, such as “classification”, “symbolisation”, “polarisation”, and mass rapes, are visible in Burundi does not mean the country is heading towards a genocide. But, as the Human Rights Council pointed out, it does make acting against perpetrators all the more important.

Yet, according to Manirambona, the jurist, nobody in Burundi has ever been prosecuted for hate speech.

Worse still, it is not uncommon for those who do post hate speech on social media to receive messages of support from government officials. Senior presidential aide Willy Nyamitwe, for example, congratulated Sylvestre Ndayizeye over his remarks, even though they were widely interpreted as an overt death threat.

IRIN