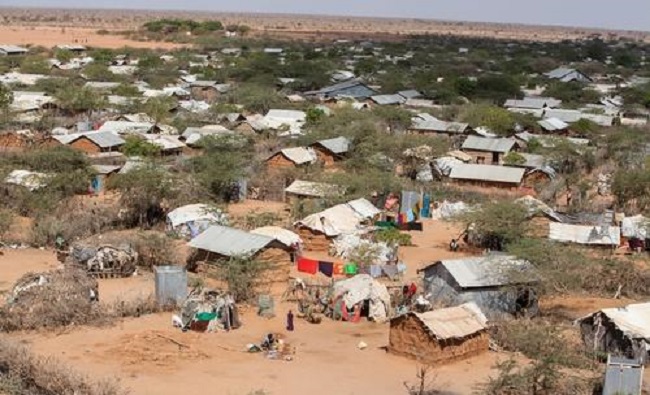

NAI researcher Sirkku Hellsten says ‘Dadaab is a further proof of the failure of international refugee policies.’

“Of course, the migration crisis in Europe is a recent development and was not predicted. Consequently, EU countries are less keen to provide money for refugees far away when they have troubles of their own on their doorsteps. Yet there needs to be a serious discussion of shared responsibilities. After all, previously the argument was that it is better to keep refugees close to their homes to make repatriation easier. What about United Nations principles of human rights – they apply to everyone everywhere,” Hellsten observes.

Cheaper solution

Supporting refugees is more costly in Europe. For instance, refugees coming to Sweden are entitled to the same living conditions as Swedes, which are quite high and expensive. In Kenya, the costs are less, and therefore European countries prefer to provide money to the UN to care for the refugees in Kenya.

“European countries then feel they have given money and now it’s up to UN and Kenya to deal with the situation. In addition, people living in the camps are probably not able to reach Europe. If the camps close some might try instead of going back to Somalia,” Hellsten points out.

Many of the refugees in Dadaab haven’t been in Somalia for years, and some were even born in the camp. It is not clear that all of them want to move back to Somalia. And what future would they have in Somalia? There is hardly a functioning state there and Somali leaders have asked for more money and time to be able to deal with the eventual repatriation of people from Dadaab. Indeed, one Somali minister visiting the camp has said that despite all the hardships there, at least the children go to school. That would not be the case in Somalia.

“No one would be happier than al-Shabaab were thousands and thousands of young people to be forced to return to Somalia with little expectation of employment or livelihood. They would represent a huge pool of new recruits. And if Somalia is now a safe place for refugees to return to, as the Kenyan government claims, how come Kenya and the African Union still have a heavily military presence there?” Hellsten asks.

A wake-up call

Everybody complains about the living conditions in refugee camps, but no one wants to take responsibility for the refugees when camps close. Neither Kenya, nor Somalia or the UN, Hellsten argues, cannot vouch for a decent living for those refugees after repatriation. Kenya’s cry is a wake-up call for policymakers to start a serious discussion about these issues.

“We need to see the big picture. I am not defending the Kenyan stand on closing the camp, after all, the human rights situation is rather serious there now. However, the country does bring issues of double standards and inconsistencies in the open. Dadaab is a further proof of the failure of international refugee policies. If Kenya gets AU and UN political support to close Dadaab, what happens next? Remember, there are many refugee camps on the continent. Will, for instance, Tanzania also ask for more money to keep its camps going? Kenya has raised an important question that must be dealt with urgently,” Hellsten concludes.

Nordic Africa Institute