Alarming malnutrition rates in Nigeria

20-month-old Ummi Mustafa and her mother, Maiduguri, Nigeria. Credit: Guy Calaf/Action Against Hunger USA)

The world may have finally woken up to the child hunger emergency in northeastern Nigeria, but the latest data shows, if anything, a deepening crisis.

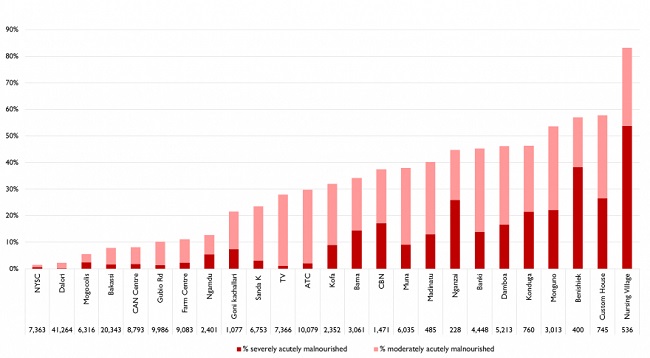

Levels of Global Acute Malnutrition recorded in July and August were well over the 15 percent threshold deemed “critical”, and, in some cases, higher than 50 percent, meaning more than half the children surveyed suffered from moderate or severe acute malnutrition.

In a special report on the “possibly deteriorating” situation in the states of Borno and Yobe, FEWS NET, a network set up by USAID to provide early warning on famine and food insecurity, said surveys and screenings indicated GAM rates “ranging from 20 to nearly 60 percent”.

“This level of acute malnutrition reflects an ‘Extreme Critical’ situation… and is associated with a significantly increased risk of child mortality,” it said. “Conditions may be even worse in areas that remain inaccessible.”

UNICEF helped to draw attention to the unfolding crisis in northeastern Nigeria in July, highlighting the fact that an estimated 244,000 children faced severe malnourishment in Borno State alone and warning that an estimated 49,000 – one in five – would die if they didn’t receive treatment.

Elizabeth Wright, head of communications for Action Contre La Faim (Action Against Hunger), which conducted several of the nutrition surveys, said the situation – not in northeastern Nigeria alone, but also in Yemen, South Sudan, and Central African Republic – represented the worst humanitarian crisis and suffering since World War II.

“We are seeing a horrifying prevalence of malnutrition that far exceeds emergency thresholds, and people are facing catastrophic levels of food insecurity,” she told IRIN by email.

The latest red flag from FEWS NET draws particular attention to places like Banki Town and Bama in Borno State, where the threat of Boko Haram violence continues to limit movement and prevent humanitarian access.

Brief respite for Bama

Not long ago a busy farming hub and commercial centre home to 270,000 people, Bama is a ghost town. One of the places worst hit by the Islamist extremist group Boko Haram, the streets are deserted, the houses on them have no roofs, and there is literally no sign of life.

A former government hospital has been converted into a camp and now holds more than 25,000 internally displaced people, mostly from neighbouring towns and villages, with some coming in from as far as Adamawa State and towns along the border with Cameroon.

In the wake of the UNICEF campaign, the crisis here enjoyed a brief spell in the international media spotlight. Bama even received a string of high-profile visitors, including Africa’s richest man, Aliko Dangote, and U2’s frontman, Bono. A range of relief items, including food, clothing and drugs, were delivered.

But most people here, especially the displaced, regard the town as neither fully safe nor ready for reoccupation, and they fear going back to villages even more likely to be raided.

Percentage of internally displaced children screened by UNICEF between 2 May and 8 August who were moderately or severely acutely malnourished

After insurgents attacked Gwoza, his hometown, in the summer of 2014, 44-year-old Ibrahim Abubaka and his family hid in mountain caves for months, sneaking back into town just after dawn to get food supplies while Boko Haram sentries were still asleep.

“We can’t go back for now because no one knows what could happen tomorrow,” Abubaka told IRIN.

Back in Gwoza, like in Bama, returnees are scared because there is no guarantee of safety as they seek to rebuild their homes or start planting again.

“Those who have the courage to go back are forced to start farming along the road and send their cows into the farming areas deep in [Boko Haram territory],” Abubaka said.

Better access needed

Wright said the information they had for outlying areas, like Gwoza, was incomplete.

“The humanitarian community does not have adequate, reliable, statistically representative data on nutrition status for many of the newly liberated and inaccessible areas of Borno. Severe access constraints have prevented humanitarian actors from reaching populations in need,” she told IRIN.

“It is vital that humanitarian actors are able to conduct technically sound nutrition assessments in newly accessible areas of Borno to quantify the scale and severity of needs and to guide the most appropriate, effective humanitarian response.”

Wright pointed out that much of the latest data was based on Mid-Upper Arm Circumference (MUAC) screenings of children under five, which can give you a good reading of the trend but aren’t as technically sound for showing malnutrition prevalence as fuller nutritional assessments.

Nutrition survey and screening results in Borno and Yobe states

Despite her caution over the data, Wright said 50 percent levels of GAM were very unusual and similar to what was seen during the 2011 crisis in Somalia when the scale and severity of hunger led to a declaration of famine by experts and the UN.

One of the few other places where similar levels of GAM are currently being seen is South Sudan, but Wright described an even more urgent situation currently in northeastern Nigeria.

“In Monguno in north Borno State, where we have launched new emergency programmes, in only four days we admitted 120 children under five for treatment for severe acute malnutrition,” she said. “By comparison, that is five times the number we admit in our emergency programmes in South Sudan.”

IRIN